In the late 1950s, Selmer M. Johnson and Hale F. Trotter independently created an algorithm – aptly named the Steinhauss-Johnson-Trotter algorithm – which generates all permutations of unique objects. Crucially, to get from one permutation to the next, only one next-door-neighbour pair of elements can be swapped, and no permutation can be repeated. Such an algorithm sounds like a tall order. It wouldn’t be a stretch to imagine that Johnson and Trotter were pretty pleased with themselves to be the first ones to discover it. Except they weren’t. English church bell ringers had been using it for over 300 years.

Bell ringing – or change ringing – is less of a quirky hobby than an endurance sport, both mentally and physically. Each bell ringer controls a huge bell, often on the order of a tonne in weight. One by one they ring their bells, then switch to a new permutation (a change) and repeat. Each ringer will remain on the same bell, it is the order in which they ring them that changes. The rules are as follows:

- In each change, a bell ringer can only switch to a position directly next to their last position.

- A permutation can never be repeated, except from the first and last permutations, which must be the bells rung from lowest to highest.

- No bell may stay in the same position for more than two changes.

For example, if we have three bells (), they may be rung as:

You might have noticed that condition three is not specified by the Steinhauss-Johnson-Trotter algorithm. In fact, this algorithm can no longer be used for bell ringing purposes since the third condition was introduced. But fear not, the bell ringers have plenty more tricks up their sleeves.

When every permutation of bells is rung, it is called an extent. An extent of seven bells is called a peal; this means permutations, rung continuously over about three hours, with almost no room for error. This is the bell ringing marathon.

The link to maths isn’t subtle here. The combinatorics isn’t hiding sneakily in the background. It is – so to speak – the humongous, one tonne bell in the room. But it leads us nicely to a combinatorial object that can give us the very answers we need to find the best bell ringing algorithms. This object is the permutohedron.

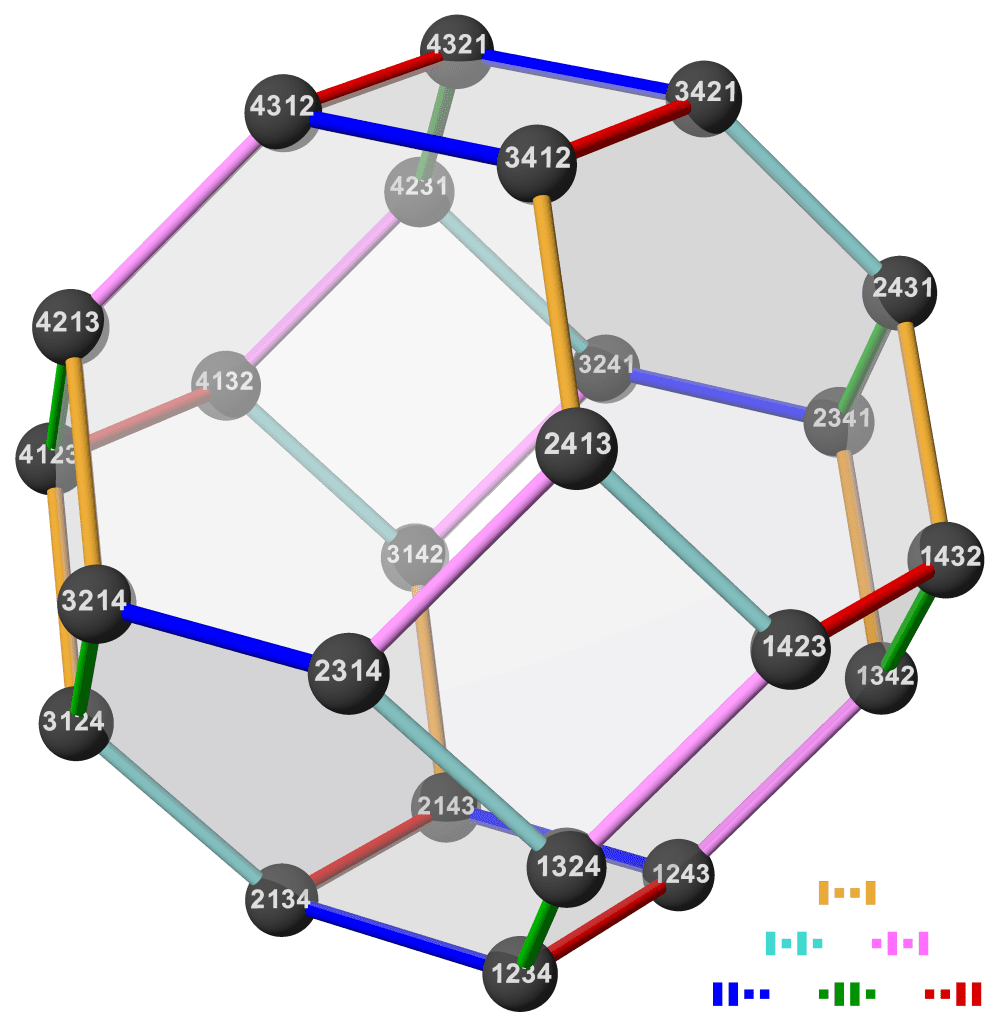

Say we have bells and we want to build a permutohedron to help our search for the perfect peal. Well, first we need to be in -dimensional space. Not so bad if we have two or three bells, perhaps a bit more taxing if we have the standard seven bells needed for a peal. But don’t worry, our permutohedron will only be dimensions itself, and six dimensions is child’s play really. For each possible permutation of the bells, we create a vertex, and the vertices are joined by an edge if they differ only by swapping two next-door-neighbour elements.

The key to finding a full peal is now right in front of us. All we need to do is find a path on our permutohedron that passes every vertex, without ever visiting any vertex twice, and ending at the same vertex we started on. Luckily, a path like this already has a name: a Hamiltonian cycle.

I feel obliged to point out that I’ve made some pretty severe simplifications here. Firstly, condition three is still not satisfied by simply finding any Hamiltonian cycle on our permutohedron. And secondly, I may have swept under the rug an important detail in bell ringing. While it is true that a bell may only swap positions with one of its next-door-neighbours in a change, multiple bells can be swapped in a single change. For example, the change

->

is perfectly legal, while in both the Steinhauss-Johnson-Trotter algorithm and in our permutohedron, this is a strictly illegal move. Once again, the 17th century bell ringers are solving more complex mathematical problems than ourselves, hundreds of years earlier. I will leave our brief look into the deeply mathematical endurance sport that is bell ringing here, for now. The subject is full to the brim with exciting maths and unsolved problems, and I fully expect to report back with more gory details in the future. But before that, I think I should go get my hands dirty and ring some bells. Watch this space…

Leave a comment