On Christmas day we sat round the table, crossed our arms, and pulled crackers on each side. In mine, I found a silver paper hat, a terrible joke, and a sparkly orange bobble (that I will be keeping). My sister had won the real jackpot; nestled inside her cracker was the magic of modern computing.

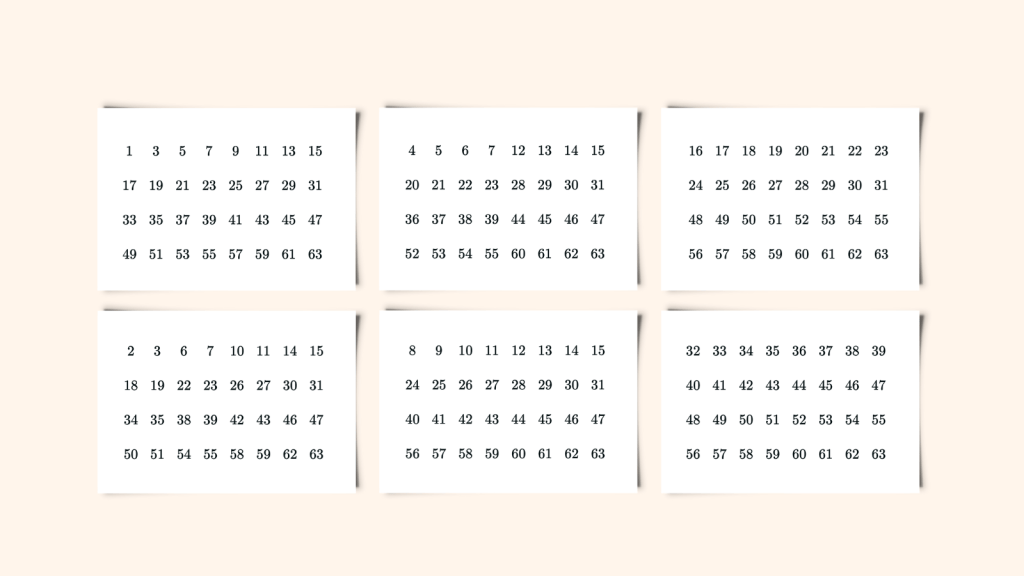

She had won a ‘magic calculator’: six pieces of card with seemingly random numbers listed in no particular order on them. A set of instructions explained how to wow your audience with a magic trick:

- Ask the audience to pick a number on any of the six pieces of card without showing it to you.

- They should then pick out all the cards which have this number present and give them back to you.

- You will then secretly add up all the numbers in the top left corner of these cards.

- Finally, reveal to your audience their number!

I did the trick a couple of times and my family were surprisingly impressed. One of them chimed in “how does it work?”

My first thought was this: after a quick look at the cards, every number from one to sixty-three is listed somewhere. For the trick to work, each number must be the sum of the top left numbers of some combination of the six cards. In other words, there must be at least sixty-three unique ways of choosing a subset of the cards. Can there really be that many ways of combining these cards?

If there were only three cards, there would only be seven ways of choosing a subset of the cards. Three ways of picking just one card, three different ways of picking two cards (you can think of this as three ways of choosing which card to leave out), and one way to pick all three of the cards.

So how about when there’s six cards?

There are six ways of picking one card.

For two cards it already gets a bit more complicated. Let’s think through it one step at a time. When we pick our first card there are six cards to choose from. When we pick our second card there are now five cards to choose from. Naively we might think this means there are ways of choosing two of the six cards. For each of the six paths we can go down initially, it branches into a further five paths. But by this reasoning, if we pick card A followed by card B, this will be considered a unique combination to picking card B followed by card A. In this game, the order that we choose the cards in is completely irrelevant, so we want to get rid of this overcounting. For two cards, every combination can be written in two ways (A then B or B then A), so we simply divide by two. That means we have fifteen ways of uniquely choosing two cards.

Now we have a rough procedure, we can use it for every number of cards.

Three cards: ways of picking three cards. But this overcounts the different ways of ordering the three cards we pick. So there are in fact ways of uniquely choosing three cards.

Four cards: ways of choosing. ways of ordering each combination. ways of uniquely choosing four cards.

Five cards: ways of uniquely choosing five cards.

Six cards: Clearly there is only one unique way of choosing all six cards.

Our grand total is ways of choosing a unique subset of the cards – the exact number we needed!

So we know we have enough combinations of the cards so that each number can be associated with a unique combination. But what about all this summing the numbers in the left corner business? Why should that always work out to give the number we want? My Dad made the observation first: “Sixty-three is . Is that important?” We looked more closely at the cards; in the top left corners were the numbers . Also known as . It was there all along – binary.

We write our numbers using a decimal system. We have unique symbols from zero through to nine, then we write the next number as . The represents one set of and the represents zero sets of . A more illustrative example: the number three-hundred and seventy-four. When we write the digits , in this way, what we really mean is three lots of plus seven lots of and four lots of . You may get a sense here that there are other ways we can write numbers. We’ve chosen our system to revolve around powers of ten. Why not powers of six? Or eleven? Or one-hundred and forty thousand three hundred and ninety nine? One of the most revolutionary questions, however, was why not powers of two?

The last digit represents how many sets of , the previous digit sets of , before that sets of , and so on… To count from one to ten we can write:

And that is the beauty of binary – we can write every number with just ones and zeroes. This is how computers work; millions, billions or even trillions of tiny switches that can either be on (representing one) or off (representing zero). We might think in decimal, but computers think in binary. And that doesn’t exclude our magic Christmas cracker calculator either! Each card carries a different power of two and can either be on (included in the combination given back to the magician) or off (excluded from the combination). By the law of binary, if we can have up to six digits, each of which can be zero or one, we can make every single number from one to sixty-three.

And there we have it, our magic calculator is actually a computer using binary to spread a little Christmas cheer.

Leave a comment